He Never Went to Art School... Now His Paintings Sell For £1 Million

Lincoln Townley was a club promoter before his appetite for drugs and sex took over. Michael Odell finds out what happened next...

Just over a decade ago, Lincoln Townley would spend his evenings cruising round Canary Wharf in London in a car full of lapdancers. He was looking for men in their fifties working in banking – men seeking an evening’s entertainment. When he found them, Townley would drive them back to the West End, install them in a booth at Stringfellows nightclub, where he was the head of PR and marketing, and the night would begin.

“A bottle of champagne for anything between £500 and £5,000 and a beautiful girl sitting next to you at £400 an hour,” he recalls. “Then of course there were the tricks of the trade. ‘Would you like to meet my friend Shirley?’ As soon as Shirley sits down, that’s another £400 an hour.”

Townley, now 51, was good at bringing in the punters. A wealthy clique of bankers might spend £100,000 in a single evening. But there were strict rules for club staff. No drink. No drugs. No touching the girls.

“Inevitably you reach a point where the big bananas from finance are your mates. They’re saying, ‘Linc, have a drink or a line with us.’ And I’m bringing in so much money I think, ‘Why not? The rules don’t apply to me. I do what I f***ing want.’ ”

If Lincoln Townley were a corporation with a website, I think you’d find “I do what I f***ing want” under the tab marked “Our Values”. It’s all there in his 2014 memoir, The Hunger, which describes his high-rolling years working for the impresario Peter Stringfellow at his eponymous club and his subsequent descent into addiction. Townley would drink two bottles of rioja, three chocolate martinis, four bottles of Stella Artois, a bottle of beaujolais, nine vodka and tonics and snort a gram of coke by 3pm each day. Sometimes he’d throw a Viagra into the mix and recounts having sex in a disabled toilet and breaking the ceramic bowl.

“I am a greedy man and greed can be a good energy if you channel it properly. Back then I couldn’t,” he says.

“Think what you could achieve in life if you were sober,” Peter Stringfellow advised Townley before firing him. That was 2012, but Townley wasn’t done yet. The same year he met the former Coronation Street actress and Loose Women panellist Denise Welch at a London nightclub. It was 6am. They were both off their heads.

“She couldn’t see the red flags because she was in that world herself,” he says. “To be honest, the omens weren’t great.”

Welch has had well-publicised issues with depression, alcohol and cocaine. She had only recently split from her husband, the actor Tim Healy, and she and Townley initially proved an explosive combination.

They drank. They fought. Welch could be found pole-dancing in a London club at 5am and attempting to get through a live Loose Women broadcast a few hours later.

“It was unsustainable for her and for me,” Townley says.

He became sober first. His best friend, the actor Marc Warren (Hustle), tried to get him to go to Alcoholics Anonymous but Townley simply went cold turkey. “Marc wanted me to believe in AA and the ‘higher power’ but to me there is no higher power, just me, so I just stopped.”

After he showed Welch a video recorded on his phone of her smashing up his flat in a drunken rage (she had no memory of it), she followed suit. “That day was the start of us channelling that dark energy into good things,” he says. “And look at the life we have now.”

The new life looks good. I am in Welch and Townley’s apartment in what used to be BBC Television Centre in west London. Davina McCall is a neighbour and Welch, 65, can walk to the Loose Women studio nearby. She’s not in – she is preparing to play Queen Elizabeth II in a one-off performance of a musical about the former Princess of Wales called Diana.

But Townley is here, all stocky, beady charisma. His look is EastEnders’ Phil Mitchell smartened up to face court charges relating to an unlicensed roadside burger van. His energy is: chastened multi-hyphenate Soho wildman (his memoir records him as a boozer, snorter, shagger and street fighter).

“This captures the energy that nearly finished me,” he says, indicating a large canvas on an easel. It depicts a demonic skeleton languishing amid the red fires of hell and is called Banker in Soho. On the walls are three smaller portraits of men in suits and ties with ghoulish melted faces. Clearly influenced by Francis Bacon, they are powerful and haunting grotesques.

“I like painting bankers and financiers because I admire greed and ambition,” Townley confides, as casually as someone explaining why they like painting tulips. “I watched the guy who bought this park his brand new Rolls-Royce Wraith on double yellow lines outside the gallery and I totally get that ‘I will do whatever is necessary to get what I want’ mindset.”

Townley’s grandfather taught him to paint and, even at the height of his addiction, he dabbled, though he hid these efforts under his bed. But as his relationship with Welch developed, she saw them and encouraged him. Even so their relationship and Townley’s new career did not meet universal approval.

“A lot of people were suspicious. They’d say, ‘Denise is a celebrity and here she is hooking up with this drinker from a lapdancing club.’”

Welch’s son, Matty Healy, is the frontman for the hugely successful band the 1975. When Townley announced his plan to quit strip clubs and make a living as a painter, Healy wasn’t impressed.

“You should have seen Matty’s face. He looked stunned and then laughed. And I get it. People would think, ‘Of course Denise’s new bloke is going to be a painter; he can do what he wants because she’s loaded.’ First, that wasn’t true. Second, I understand that when a celebrity starts dating someone not from that realm everyone thinks, ‘What are they after?’ But I also thrive on being an outsider. I never doubted I could sell my work. Even after 93 rejections from galleries, I felt each ‘no’ was getting me nearer to hearing a ‘yes’.”

His stepson is a superstar but has also struggled with heroin addiction. That must make family get-togethers pretty intense. Everyone is in recovery.

“If we have one thing in common it’s that we are all trying to control our dark energy,” he says. “We all know the consequences if we don’t.”

Townley no longer has to prove himself. He has just sold Banker in Soho to a banker in Soho for £350,000. The smaller triptych titled Greed has sold for £450,000. But these Baconesque works are just one side of his output. He has also enjoyed extraordinary success with celebrity portraits. These are different, more straightforwardly representational “pop art” works. The first person to agree to a sitting? Russell Brand.

In 2013, Brand’s portrait was sold in aid of the charity ABRT (Abstinence Based Recovery Trust) for £20,000. Brand put Townley in touch with his contacts in Los Angeles.

Townley promptly flew to California and the first person to take his call was the actor and recovering addict Charlie Sheen. Townley met him, then went back to his room at the Standard hotel to paint his portrait. Sheen loved it so much he called his friend Nick Nolte. Same thing. Townley met Nolte, then painted him.

“Nick was very supportive. He rang the British boxer Gary Stretch, who trains with Mickey Rourke. I met Mickey in a bar and painted him next.”

By the end of the trip he had added Harry Dean Stanton and Al Pacino.

Meanwhile back in the UK, Denise Welch’s godfather, the writer Ian La Frenais (Porridge, Auf Wiedersehen, Pet), put him in touch with his friend Michael Caine. After being painted by him the actor declared Townley “the next Andy Warhol”. Bafta commissioned him to paint portraits of everyone from Kenneth Branagh and Matt Damon to Cate Blanchett and Phoebe Waller-Bridge.

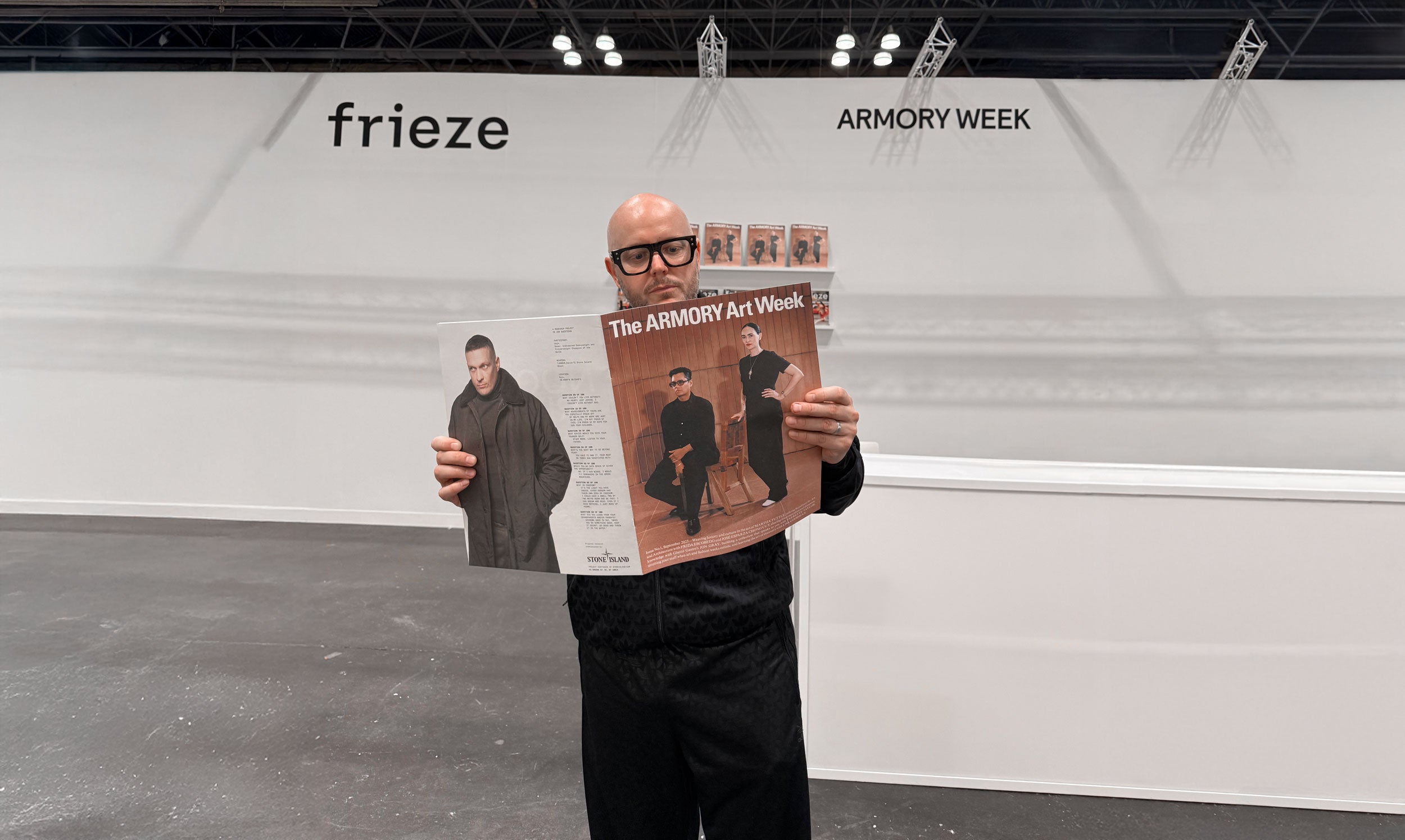

It’s incredible, I say. In 2012 he was drunk, broke, finished. Now his work sells for £1 million a pop (a New York collector paid that price for his portrait of Diana, Princess of Wales) and he will shortly be exhibiting at the Venice Biennale.

“From the outside it looks incredible, but coming from nothing is actually the thing that a lot of my subjects respond to,” he says. “I’ve talked to Sam Jackson [the actor] and Jackie Chan about this [both are Townley subjects]. Hollywood is an incredibly hard place to make it. I paint the hell I went through and that reflects the hell these guys experienced.”

Nolte, Sheen, Rourke: he has painted a lot of recovering addicts. But post- #MeToo, people are more vigilant about policing the line between hedonism and abuse. His first client, Russell Brand, is now a disgraced figure. Did Townley ever fear his own appetite for sex, drugs and booze might get him into trouble?

“It is dangerous to have those appetites,” he says. “But it’s hard to say what might have happened. I had to change, but I can’t speak for anyone else.”

Townley’s story is compelling, but is the art any good? A London gallerist I speak to says, “It’s not very original. It reminds me of when Damien Hirst tried to paint like Francis Bacon, with a bit of Basquiat thrown in. It’s not groundbreaking, but people often respond to artists’ stories as much as the actual work.”

Townley had an unpromising start in life. He was born in Hackney, east London, where his dad was a doubleglazing salesman and his mum a housewife. When Townley was 14, his father died of a heart attack in front of him. Thereafter his mother told him he couldn’t go to art school. She needed him to help pay bills.

Townley made doughnuts at a bakery and then worked at a garden centre. By 19 he was a married father of one (his son Lewis is now 31), and by his late twenties the head of sales for a van rental company. Of course, a van is just a van. But give Townley a fleet of Transits and it becomes an extension of his personality.

“I was a f***ing good salesman,” he asserts. “I had that hunger to succeed. Van rentals is the kind of world where you apply for a job and they want to know why you haven’t got points on your driving licence. No points means you’re not driving fast enough, not taking enough risks to get the deal over the line.”

It’s how he came to work for Peter Stringfellow. As a sales director, Townley became a master at incentivising clients.

“Most sales managers would send out a £200 Christmas hamper. I would take my clients for a night at Stringfellows. These guys haven’t lived the good life. They could not believe what I was showing them.”

First just a handful came, but after a few years Townley would hire out the whole place.

“The money they spent was incredible. Peter [Stringfellow] would sit on his throne at the end of the table and the girls, the booze – it was like ancient f***ing Rome.”

Stringfellow hired Townley because of his ability to sell. As Townley says in his book, “It’s no different from selling vans.”

So, he admires risk-takers and greed. But his attitude to sex is jaw-dropping. I’d say Townley had a caveman mentality if I didn’t think the National Union of Knuckle-Draggers and Neanderthals would write a stiff letter of complaint. “If it was there to take, I’d take everything,” he says. “I wanted to be remembered by women. I wanted them to come back.”

I need a beta blocker to get through a chapter in his memoir titled Nutella Nights, and try my best to empathise with Townley’s personal brand of regret (“No amount of anal sex could raise my spirits”). I also decide that, as an addict, Townley was Martin Amis’s antihero John Self from the novel Money made flesh. But other aspects of his sexual appetite are truly baffling. A night of passion with a lady called Fay gives a new meaning to Fifty Shades of Grey.

Townley was in his mid-thirties. Fay was “north of 75” when he met her while she was enjoying a night out in Soho with her daughter. But Fay’s daughter needed to go home to her children, so Townley offered to take Fay out for a drink. He describes them kissing in a taxi back to “her place”. However, Townley blacked out before they could have sex and woke up disorientated in Fay’s bed the following morning.

“That’s when I see those mobility railings everywhere and that red emergency cord you pull to raise the alarm after a fall. I realise I’m in a care home, so I grab my stuff, push my way past all those giant armchairs they have in the day room and run for it.”

It sounds like a terrible Christmas cracker joke: why does a man running a lapdancing club pick up an 80-year-old?

“You can have fun with young women, but you can’t have a deep conversation because they don’t have life experience,” he explains. “The truth is, you’re never lonely with a granny. They know a lot.”

Denise Welch is 14 years older than Townley. When they began dating the tabloids called him her “alcoholic toy boy”. Yet their relationship has survived against the odds (they married in 2013, on the anniversary of one year’s sobriety) and these days they appear cosy. Like a normal middle-aged couple.

Welch has spoken out about how the hormonal changes of the menopause have alleviated the acute depression that once plagued her life. Being in a sober postmenopausal relationship, has he had to calm down a bit?

“No. We are very sexual and my sexual energy hasn’t changed. We are still in that marketplace. Sex is extremely important to both of us. We’re not hanging off the chandeliers, but it’s still there big time. I cannot live without sex.”

Theirs is an extraordinary post-addiction survival story, but is Welch really OK? I ask because we are talking the day after she was quoted in a newspaper reporting an incident in New York – the sort of incident one associates with people struggling, in this case literally, to hold their shit together.

Last year she and Townley were in New York to see the 1975 play at Madison Square Garden. Before the gig Welch noticed people in the street looking at her. She thought it was because Matty is such a huge star. “So she gets back to the hotel and is telling me she’s getting loads of attention,” Townley relates. “But then she bent over and I said to her, ‘You do realise you’ve shat yourself, don’t you?’ Den was wearing cream trousers. But so what? It happens. We laugh about things going wrong. Because once you’ve been to the dark side, nothing can really hurt you.”

Lincoln Townley will be showing his “ten-year celebration” Banker collection in the Palazzo Bembo for the 60th Venice Biennale from April 20-November 24, 2024 (labiennale.org/en/art/2024)